Quality Assurance Rubrics to Support Teacher Agency

Quality Assurance rubrics are multifaceted, and sometimes controversial, tools in higher education.

Quality Assurance rubrics are multifaceted, and sometimes controversial, tools in higher education. Course developers, curriculum administrators, and accreditation agencies use them to design analogous academic programs within and across institutions. Quality Assurance (QA) rubrics like the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric also encourage pedagogical reflection and support course revision. QA rubrics may be perceived as equitable because they promote transparency and compatibility across teaching practices. However, they can also invoke a sense of trepidation in some educators who view them as imposing on professional agency.

While this fear is valid in some cases, is it applicable to all QA rubrics across the board? Or are there some rubrics which impede teacher agency and others which support it? My view is that it is not simply the rubric but also the context in which the rubric is used, and the practices which govern its use that determine its impact on teacher agency. A rubric that supports teacher agency will be carefully developed and carefully applied as a heuristic rather than a prescriptive tool. Following are several guidelines for creating and implementing such rubrics.

The Multifold Path of a Well-Designed Rubric

First and foremost, it is important that a rubric be developed with flexibility in mind. A ‘heuristic’ rubric, in this sense, is like a map showing specific destinations and providing multiple pathways between them. A prescriptive rubric, on the other hand, would be a map with definitive routes between destinations, lacking the ability for the traveler to veer away from the intended route. This means that a balance exists between linguistic precision and room for interpretation with regard to rubric criteria.

The problem that often arises with flexible rubrics is that their criteria can be interpreted as “vague.” In my opinion, vagueness is simply an invitation for the educator, or professional community, to define and apply the descriptors in a way that is useful for them. Each criterion is a guideline with (ideally) clearly defined parameters, but the fleshing out of those criteria should continue at the individual level or the program level, through harmonization processes.

At the University of Arizona, we are implementing harmonization sessions within our community of trained reviewers to determine how to implement the Quality Matters rubric in a way that suits our institutional context and the interdisciplinary nature of our university. Also, in agreement with Quality Matter’s defining principles, the course evaluation process is designed to be supportive, iterative, and constructive rather than punitive. Our instructional designers work with instructors to meet rubric standards in ways that suit their individual needs and teaching styles.

The Democratic Process of Rubric Building

In addition to flexibility, it is important to develop and use a QA rubric democratically, meaning that the voices of multiple, diverse stakeholders contribute to its creation, and its criteria are regularly updated and vetted for equitability. These principles can be reinforced using pedagogical frameworks like the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework. UDL synthesizes concepts from accessibility, UX, and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) literature to ensure that a rubric or pedagogical approach supports all learners. Frameworks like UDL enable instructors to apply suggested practices in a manner which fits their unique styles and preferences.

The QM Rubric was designed by a group of practitioners and researchers and is updated continuously every two to three years to ensure that its content stays current. It draws from current teaching and learning literature in the creation and maintenance of its Standards, and it incorporates UDL as a focal point for General Standard 8. The QM internal review process is also structured in a way that allows subscribing members to adapt the process to suit their institutional needs, for instance through harmonization practices, and one of the core tenets of the review is the concept of majority rather than consensus. If at least two of the three reviewers on a review team decide that the course meets a Review Standard at least 85% of the time, the course meets that Review Standard and receives the full amount of points associated with it. These factors support a democratic design and implementation of the rubric.

Context is Key to Implementation

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it is essential that the processes developed around the application of a QA rubric invoke stakeholder buy-in. A rubric should be adaptable to its intended context, leaving enough “wiggle room” while still meeting the general guidelines. This is often the most difficult aspect of QA rubric development, as no two courses, programs, teachers, or institutions are exactly alike.

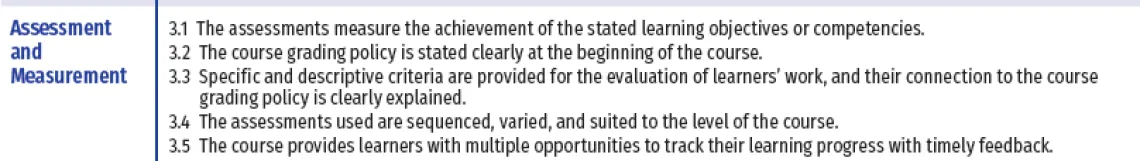

Course assessment practices, covered in General Standard 31 of the QM Rubric, vary markedly across disciplines. Ginger Hunt, Senior Director of Online Learning and Instructional Design at the University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law, and her team2 identify grading policies and syllabi as a key difference in how the QM rubric is applied to Law courses. Ginger explains that Law school courses are governed not only by UArizona and ABOR policies but also by the American Bar Association (ABA). The ABA has standards that they need to follow, which include grading schemes. Due to these standards, as Ginger explains, “our syllabi must include detailed grading schemes for all students following the College of Law student handbook, which aligns with ABA standards and main campus grading policies.” Ginger often has QM reviewers who question the grading schemes in her courses because “they need help understanding the grading policies and the fact that, as a professional school, these are additionally governed by an outside agency.” This is just one example of how context impacts the way that the QM Rubric is applied.

General Standard 3: Assessment and Measurement (See Footnote)

As another example, Lindsay Lutman, an instructional designer and QM course reviewer at UCATT who works with STEM courses, outlines the nuance of reviewing STEM courses using the QM rubric:

One might turn to the definitions of puzzles and problems as described by Alan Dix,” who offers that puzzles have one solution and learners are equipped with all of the information required to arrive at that one solution. In contrast, problems have multiple solutions (or no solution) and are plagued by excessive or insufficient information. Problems challenge learners to negotiate and redefine the challenge in order to arrive at a justifiable or optimized solution. They are typically assigned as part of a larger multi-week or semester-long project in which learners analyze, evaluate, and create. Problems are also complex in that they often contain puzzles.

The challenge for STEM faculty is to provide specific and descriptive evaluation criteria [Standard 3 of the QM Rubric] that compliment these assessment characteristics, without (1) overwhelming learners with evaluation criteria, (2) hampering diversity of thought and creativity, and (3) giving away the solution. Providing “specific and descriptive” evaluation criteria for problem-type assessments that are ambiguous and non-formulaic by design is a delicate balancing act. Rubrics and checklists are two tools typically employed in the [QM] evaluation of problem-type assessments. Utilizing industry standards and guidelines to define rubric criteria and indicators is one effective way to create specific and descriptive evaluation criteria that does not affect the intention of a problem-type assessment. However, these types of evaluation tools often do not provide sufficient information on how (or if) the puzzles nestled within the problem might be evaluated.

As you can see, assessment practices, in particular, are incredibly complex and often bound by discipline. This necessitates a QA rubric which is malleable enough to adapt to numerous academic contexts within an institution.

Caveats: Everyone is Never Happy

Despite the multitude of reasons for implementing a Quality Assurance process, there will always be caveats. It is important to acknowledge the limitations associated with complex procedures like online course evaluation.

Caveat 1: No QA rubric is perfect - there will always be critics: At the end of the day, there is no “one size fits all” solution for course evaluation, and there is no perfect rubric that will fit all circumstances. There are quite a few well reasoned arguments against certain rubrics, such as the concern that they may not align with certain assessment practices, and that is ok. Part of supporting teacher agency is affording the opportunity not to join the community.

Caveat 2: Rubrics are (generally) not objective: The rubric is a tool, and, like any tool, it can be wielded subjectively by each individual. Even with its 85% rule, the QM rubric is still a qualitative instrument. As a heuristic, the QA rubric can provide a way to think about online course design. The practical application of the rubric standards, however, is ultimately the creative expression of the user, within the parameters of each descriptor.

Caveat 3: Rubrics need to be updated to reflect emerging discourses: Especially in online and hybrid learning environments, pedagogical theory continues to evolve in response to the ever changing technological and social landscapes in which we live. The rubric of ten years ago may not work for today’s educational environment. While this caveat does not apply to the QM Rubric, it may extend to broader discussions about QA rubrics.

Conclusion

The most sustainable path to implementing a QA rubric rests on its bottom-up adoption within the institution, coupled with top-down support and guidance. Requisite to this approach is successful community building. At the University of Arizona, we are committed to building a QM/QA community organically through provision of support and incentives to the instructors who work with us. We offer a variety of free workshops, webinars, and Just In Time trainings. We compensate reviewers in exchange for taking the necessary trainings. We organize regular meetings for reviewers and workshop facilitators to harmonize and share practices. We are also rolling out a new QM Fellowship program with the aim of recruiting diverse QM faculty ambassadors from a variety of colleges across campus. Furthermore, we use an iterative course amendment process in which our QM trained instructional designers help faculty update their courses until they meet the Standards. We are still in the beginning stages of this community building, so please stay tuned! Communities of practices take time to evolve.

Hopefully this article has provided some food for thought regarding the complex nature of Quality Assurance rubrics and institutional practices. There will likely always be debate over such practices, but there is also widespread agreement that when online/blended courses within an institution meet the empirically demonstrated benchmarks of Quality Assurance, there will be higher levels of enrollment, completion, overall student performance, and student satisfaction. After taking this into consideration, do we not owe it to our students to strive for common Quality Assurance goals in our courses?

Footnote

- Quality Matters (2018). The Quality Matters™ Higher Education Rubric Sixth Edition. MarylandOnline, Inc.

- Assistant, Director of Online Learning and Instructional Design, John Savery Madden.

Instructional Designers, Matt Olmut, Teresa Eckley, Nicole Beaver, Miriam Aleman-Crouch.